Berthold Romanovich Lubetkin. Architect 1901 - 1990

In 1917 Lubetkin enrolled in a private art school where he and his friends were inspired by the Revolution and when their art school closed, they enrolled in the SVOMAS system of free workshops, which offered free art training to everyone over the age of 16. Influenced by his teachers Rodchenko and Popova, and the work of their fellow constructivists, Tatlin and El Lissitzy, Lubetkin experimented with sculpture. It was here he first investigated design and architecture.

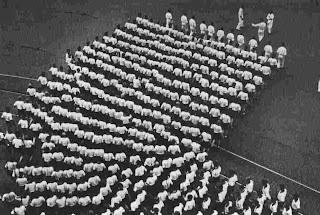

Rodchenko

|

| Rodchenko - Parade of the Dynamo sports club. 1928 Aleksander Rodchenko was a Russian artist, sculptor, photographer and graphic designer. |

|

| Rochenko - Photomontage 1924 for a Moscow publisher |

Popova

|

| Popova - Fabric samples 1924 |

Tatlin

|

| Vladimir Tatlin was a Russian and Soviet painter and architect. |

El Lissitzy

|

| El Lissitzky, was a Russian artist, designer, photographer, typographer, polemicist and architect. |

In 1922, Lubetkin left russia to move to Berlin where he enrolled at the Berlin textile academy. He also used his time to study modern construction techniques, particularly reinforced concrete, which were considerably more advanced in Germany than Russia.

In 1923 he moved to Poland to study architecture at Warsaw Polytechnic and in 1925 moved to Paris to complete his studies at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he discovered Le Corbusier, who became a huge influence in Lubetkin's work.

It was in 1931 that Lubetkin moved to London and discovered a new generation of young architects eager to experiment with the ideas of the continental modern movement. Lubetkin believed that architecture was a tool for social progress. He joined forces with the young architects Francis Skinner, Denys Lasdun, Godfrey Samuel and Lindsay Drake to form a group called Tecton.

|

| Members of Tecton photographed in 1938: Fracnis Skinner, Eileen (secretary), Margaret Church, Berthold Lubetkin, Carl Ludwig Franck, Fred Lassere, Lindsay Drake |

The first Tecton commission in 1932 was a Gorilla House at London Zoo in Regent’s Park. The architectural possibilities were fascinating, and Lubetkin was able to indulge his fascination for incorporating movement into buildings by designing sliding and revolving screens, to create a controlled environment to protect the gorillas from human infection. He built the house in his favourite form, a circle. Determined to build the circule in concrete, Lubetkin contacted the Parisian civil engineers, Christiani & Nielson, who referred him to their London representative, Ove Arup. Sharing Lubetkin’s zest for experimentation, Arup made an inspired contribution to the Gorilla House and they began a lifelong collaboration.

|

| London Zoo Gorilla House - 1932 Now home to lemurs. |

|

| Lubetkin worked with civil engineer Ove Arup, who founded the engineering group Arup. Arup was the design engineer for the Sydney Opera House 1957-1973. |

After the success of the Gorilla House, Tecton was commissioned to design a Penguin Pool for London Zoo. Lubetkin conceived it as a stage set with walkways for the waddling penguins and a spacious pool where they could show off their speed and grace when swimming.

|

| London Penguin Pool - 1934 Sadly the penguin pool is now empty. |

Tecton was then invited to design two zoos: the first at Whipsnade in Bedforshire and the second at Dudley in Warwickshire.

Commissioned by the Earl of Dudley in 1935, the zoo took 30 months to complete, and opened in Spring 1937. Lubetkin designed the enclosures in such a way as to emphasise the steep inclines and densely wooded slopes and he sought to create enclosures that would bring out the most extrovert and entertaining traits in the animal’s behaviour. There were originally 13 Tecton structures including:

The Entrance Gates, Penguin Pool, Polar Bear Complex, Bear Ravine, Sealion Pool, 2 Cafes, Restaurant, Bird House, 2 Kiosks, Elephant House and Reptilary. Unfortunately the penguin pool deteriorated to such an extent that in 1979 it had to be demolished.

|

| Dudley Zoo entrance 1937 |

|

| Dudley Zoo Polar Bear Complex 1937 |

In 1935, Lubetkin worked with Ove Arup & designed Highpoint 1, a luxury high rise apartment complex in North London, which was to define a new ideal for urban living. It was hugely influenced by Le Corbusier, and the heating, refrigeration and other functional facilities were designed to be communal.

|

| Highpoint One |

Another year later, Tecton was appointed to design The Finsbury Health Centre. He was determined that the design of the Health Centre would encourage the public to become healthier.

|

| Finsbury Health Center |

|

| Lubetkin's design idea that the sun would shine through the glass-brick walls and encourage people to be healthier. |

When world war 2 began, Tecton was diverted into designing the much needed air raid shelters. Architectural commissions dissappeared and Lubetkin moved to the Gloucestershire countryside where he and his wife Margaret looked after a succession of hippos, chimps and other exotic animals which were evacuated from London Zoo.

After the war Tecton designed a series of public housing schemes including the Spa Green Estate and the Priory Green Estate.

Tecton disbanded in 1948, and became Lubetkin, Skinner & Bailey.

Lubetkin's post-war career failed to regain momentum, and in 1949 Lubetkin resigned after his vision of redefining the modern town was met with red tape and bureaucratic opposition.

In 1982 Lubetkin was Awarded a Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

No comments:

Post a Comment